Bonjour tout le monde,

It’s been a while! A special Hola and welcome to the subscribers who joined us via my guest post on my Substack friend Sarah’s Can We Read? newsletter last week. If you haven’t seen it yet, I’m re-sharing that post below—read on for tips and reflections about reading in multilingual families.

Can we read? is for you if you love children’s books (in English) and reading with kids. Sarah truly knows her stuff and shares a wealth of practical suggestions, book reviews, interviews with authors, and more. You can subscribe right here:

Let’s begin!

This post is for you if you want to juggle reading in multiple languages at home with ease and intention. I speak from my experience as a mum in a family that speaks three (sometimes four) languages at home. And because I’m winging it a lot of the time, I have also asked actual pros for insights and practical tips that you can tailor to your tastes and situation.

Let’s start with your family language setup

What’s the dominant language and the minority one in your family? You might be acutely aware of this if you’re the only speaker of your language in your kids’ life, and have been thrown into a role as de facto guardian of a minority language/culture at home. It takes awareness and effort to maintain multiple languages; that’s true on a macro scale (like a country), and also on a micro scale (like a family).

“Even in bilingual communities, family home reading practices may exacerbate uneven development across children’s two languages,” says researcher Ana María González Barrero in a 2021 study of 66 French–English bilingual families with 5-year-old children in Québec. González Barrero, now an assistant professor in the school of communication sciences and disorders at Dalhousie University in Canada, found that families who are less proficient in one of their two languages tend to have more books, more reading sessions and longer reading sessions in their dominant language. She writes:

Parents need to be aware of the tendency of bilingual families to support the dominant language, as they may wish to consciously allocate more time for reading to children in their non-dominant language and provide access to more books in the family’s non-dominant language.

Of course, we’re busy people with finite resources and energy and do not want family reading to be a chore. To make this as easy as possible, I’ve asked my friend Élodie Misrahi for advice. She’s thought deeply about how to handle books and other resources in plurilingual environments—both in her work as a teacher-librarian and trainer in international settings, and when raising her bilingual children.

Let’s get practical

What books to get

Obviously, I hope you get books that your kids and you truly enjoy, no matter their language ❤️. Let’s look at specific considerations for multilingual families:

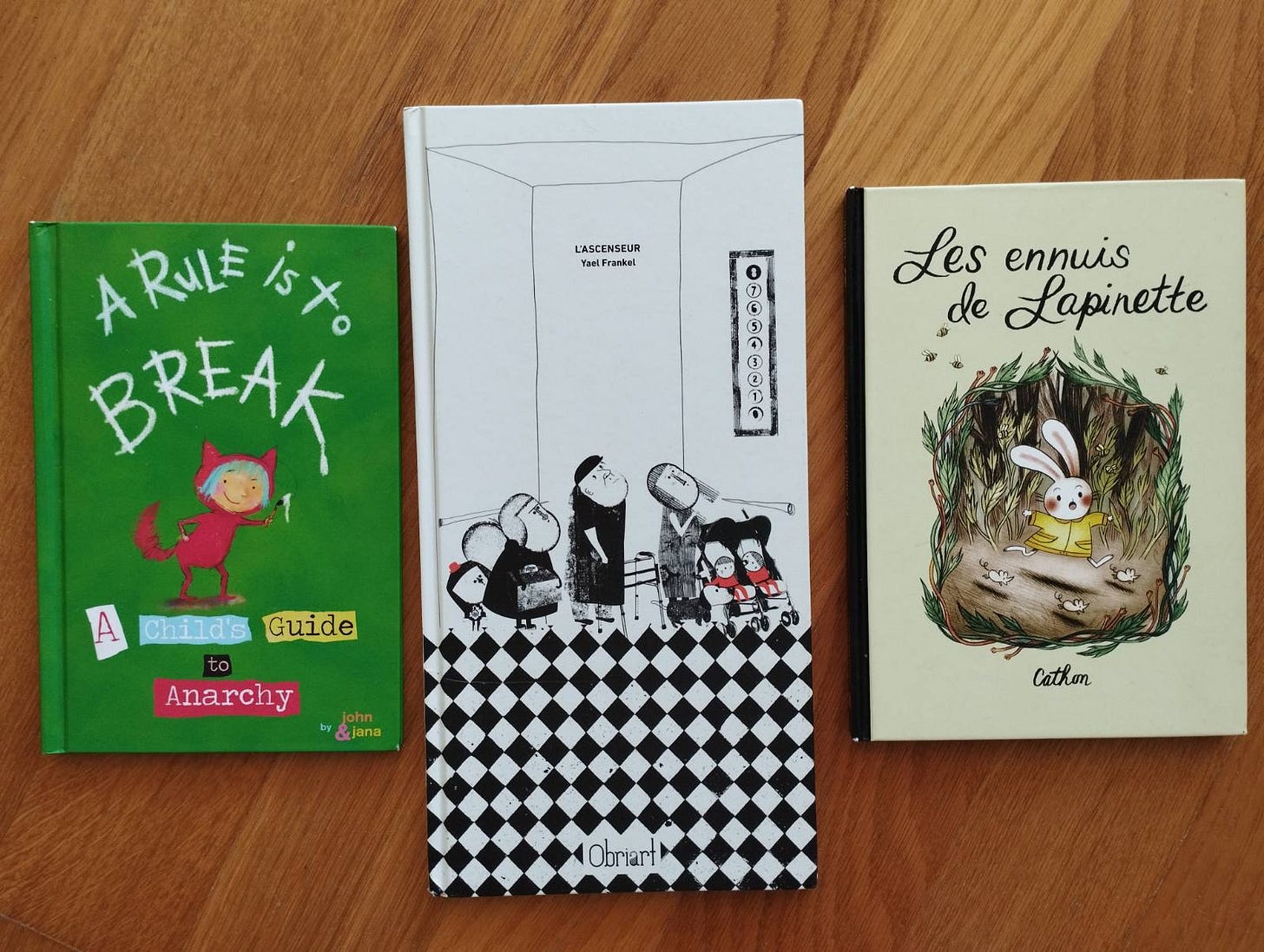

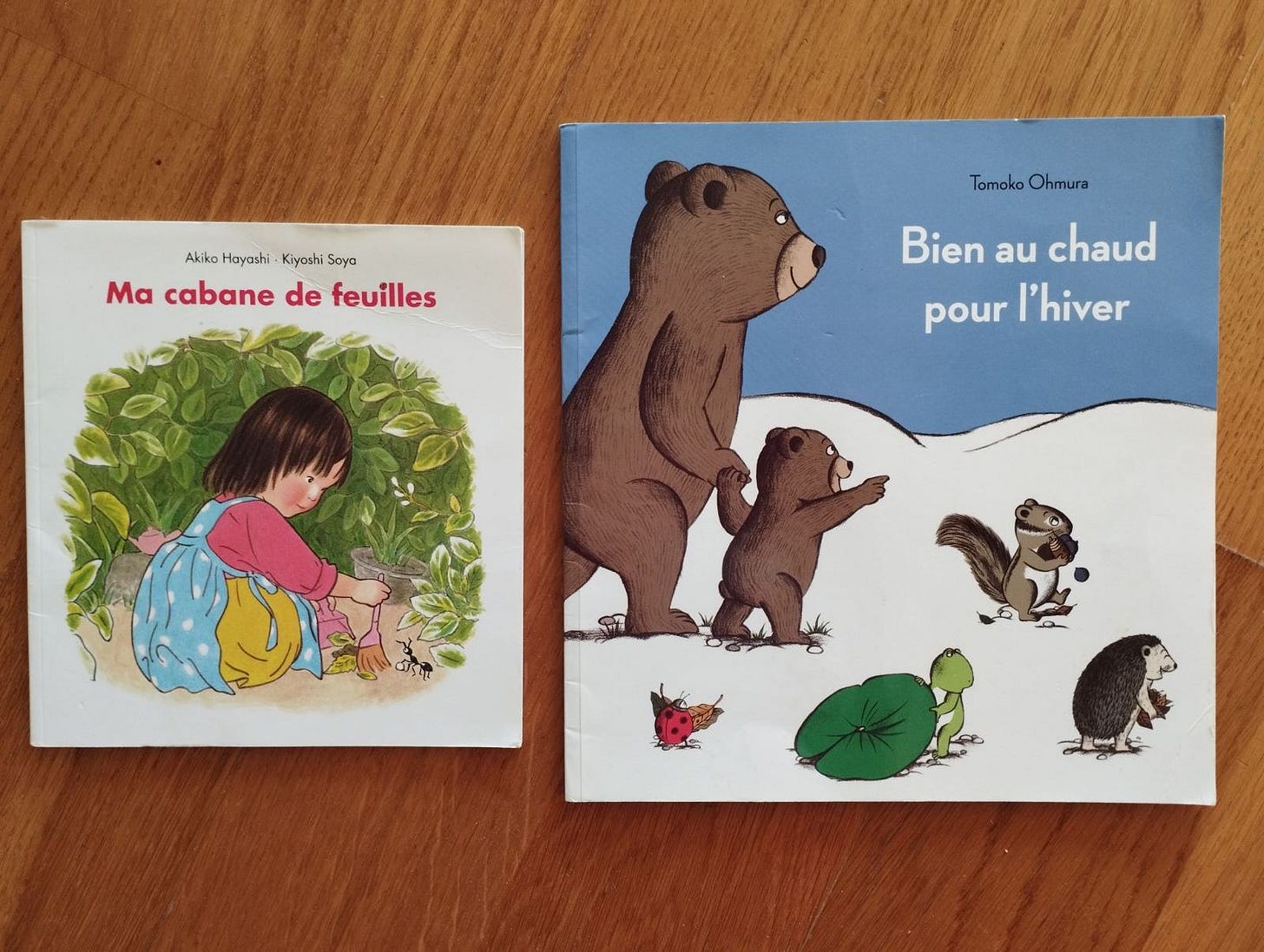

Should we ban translations? I confess I'm an original version snob. For children’s books like for any book, if we can access and read the original, brilliant! But forgoing all translations would mean we’d lose out on so many wonderful stories. For instance, I don’t speak Japanese and am grateful for translations of books by the likes of Akiko Hayashi, Kiyoshi Soya and Tomoko Ohmura.

We also happen to own the same few books in two different languages, and it's fun to compare and contrast them.

Let’s not forget books without text! They’re especially great to gather around, across ages and languages.

Some (almost) text-free books that are well-liked in our home include Pippa Goodhart’s You Choose and the Polo series by French illustrator Régis Faller (these are fantastical stories that you and the kids can narrate yourselves).

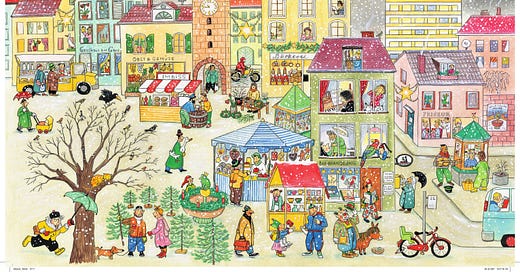

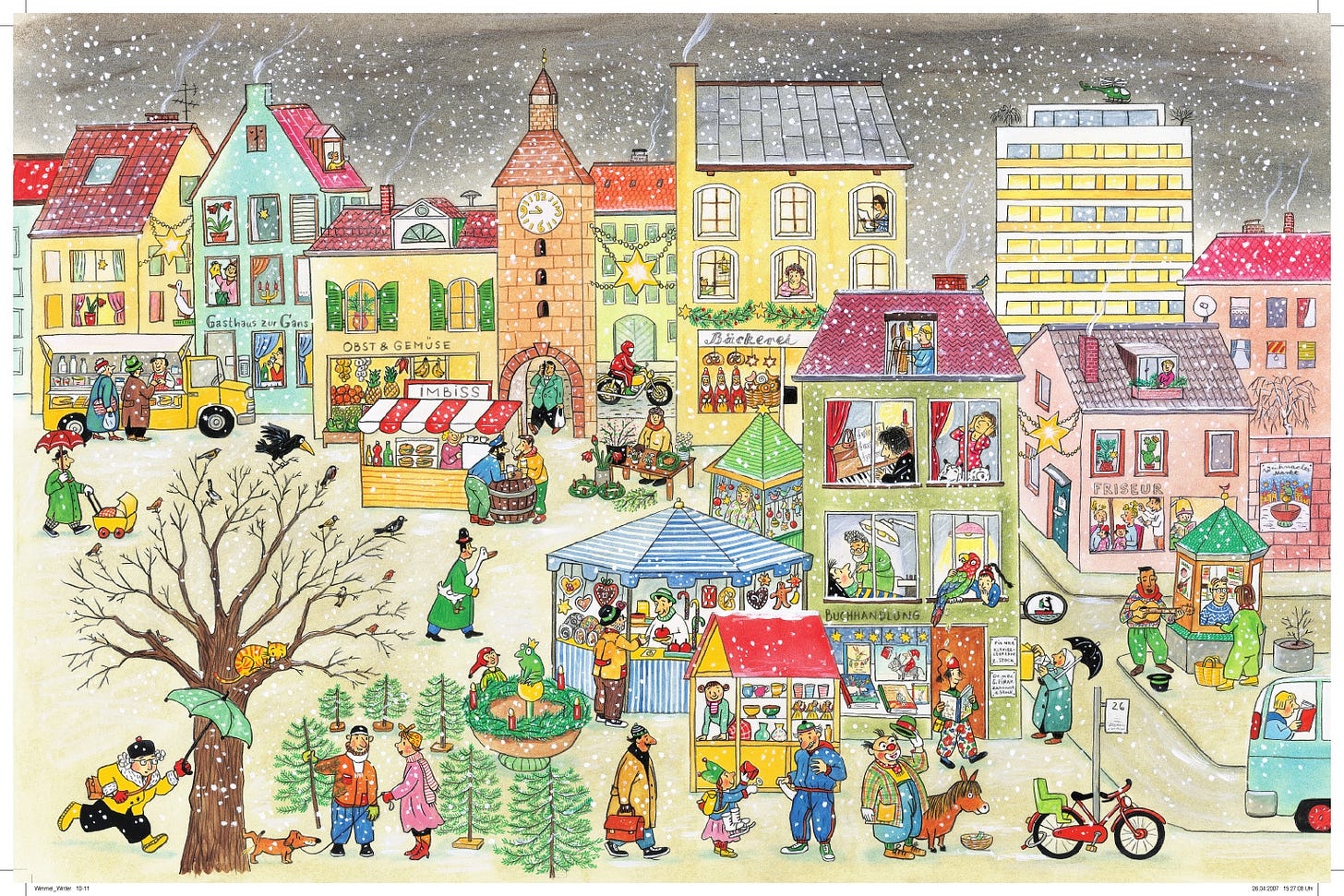

We have also spent hours marvelling at all the details in these library finds: the four seasons books by German illustrator Rotraut Susanne Berner…

… and La Ciutat (the city) and El Camp (the country) by Catalan illustrator Roser Capdevila:

To help build up our kids’ lexicon, shall we favour illustrated vocabulary books [we call them imagiers in French; I don’t know an accurate English word for them] rather than stories? Some are lovely (I like this one we received as a gift!), but let’s be frank, some imagiers feel like tedious flashcards for toddlers. Élodie says she favours “books that give access to [a language’s] culture, stories that stimulate imagination, or rich nonfiction books.”

How to get the books

(…besides the obvious giant online retailers, that is!)

Ask friends and relatives for books in your shared language as hand-me-downs or gifts. If you’re a visiting friend or relative, bring all the books!

Raid your local libraries, for real. (Élodie’s local library in France has a dozen books in Spanish: “that’s not much, and at the same time, if you borrow one per week and rotate them, it’s actually not bad,” she says.) Visit other libraries. Ask your librarians! Explore the depths of the online catalogue. My region’s public libraries are all connected, and I can request books from any of them to be sent to my local branch. Maybe yours have a similar system?

Buy second-hand. Flea markets and garage sales can be frustrating when you look for books in a specific foreign language. I’ve bought used books from online marketplaces like Vinted, which I do realise generates unwanted waste and carbon emissions to ship books across Europe (and is also very convenient when searching for a particular book 😅).

Search for book (or magazine) subscriptions in your language. As a toddler, my eldest received one of the best gifts ever: a book subscription from L’École des Loisirs, i.e. eight carefully selected books throughout the year. It’s just one of many such subscription offerings out there, maybe there’s one in your language, too?

How to store the books you do get

As with toys and foods, book rotation is your BFF. From a high shelf to a low one, from a bedroom to the toilet: rotating books works! It helps you to make the most of your library whatever its size, to keep family reading fresh and entertaining… and to nudge children towards books in a language that you feel needs attention.

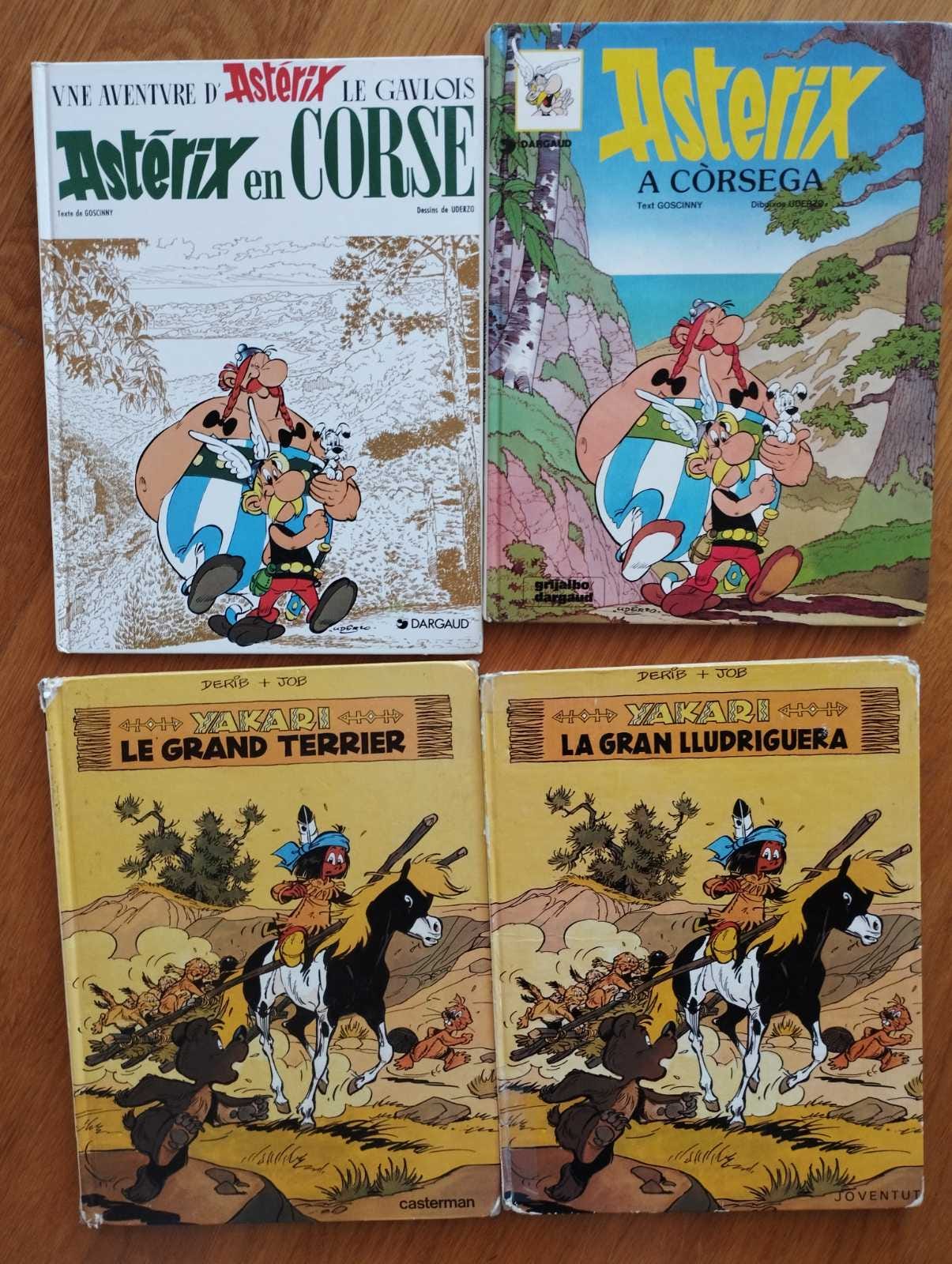

One day, I decidedly sorted the kids’ books by language: that system lasted maybe 36 hours. It made zero sense to my eldest, who was four at the time. As Élodie points out, little kids don’t go around looking for a book in a particular language (neither do I, to be fair!): they go browsing for an Astérix album, or searching for that Horses and Poneys book. It makes more sense to group books by theme (across languages), where children will actually look for them, and also stumble upon interesting, related books in the vicinity.

As for the very practical stuff: by size, by colour, in a basket, on a shelf… Choose whatever system works for your family so that your kids do access the books. I also like the sticker system at my son’s multilingual school library: one colour per language, except for books in the school’s dominant language, which bear no sticker.

Let’s read!

Both the quantity and quality of your reading sessions matter to support literacy development in children, González Barrero told me in an e-mail. And if you or your child don’t feel like reading, she suggests looking for “a different way to provide high-quality language interactions such as playing, storytelling, etc.” (Also I reckon it’s okay to say: “I’m really tired right now, shall we cuddle and talk about your day?” or “That book’s in Russian/Arabic/etc., ask grandpa!”🤭)

To switch or not to switch

You’ve probably heard about the “one person, one language” (OPOL) principle, whereby each adult should stick to their native language for consistency. If you’re part of a multilingual family, you also know how it is in practice: y’all end up mixing things up1, at least some of the time. Linguists call this codeswitching: alternating between languages in a single conversation (or reading session). “Codeswitching is a natural behaviour in bilinguals, and parents should read books to their children in the language they feel more comfortable with,” says González Barrero2.

Sometimes, I’ll read aloud in my native language when the book is written in another, like a UN interpreter of El Monstre de Colors. This is neither a practice I recommend nor a habit to ban, it’s something I found myself doing—and that González Barrero also observed in her study. As Élodie points out, this will also depend on your own situation: your language/translation skills (and theatrical) abilities, your tastes, the style of the book at hand, your energy levels, etc.

By the way, being flexible and pragmatic about OPOL applies to all caregivers! I remember my eldest at 3 years old, begging my mum to read a book in a language she doesn’t speak—which she patiently did. I found this both endearing and irritating (“that’s silly, she should be reading in French”). But it can be a cute way to bond, reading Yakari and giggling about granny’s accent together.

I hope you’ve found some ideas and encouragement here. Try things out, take what works for you and your family today, and leave the rest! I hope you have fun sharing books with the children you love ☀️.

Coming up (slowly!) on Home Mixed Home: A post about intercultural baby naming, and an interview with a Czech-Franco-German family that brought tears to my eyes. If you haven’t already, make sure you sign up to receive them in your inbox:

Go read my interview with Max Antony-Newman to set your mind at ease about this!

González Barrero points to these two studies showing that different types of translation or codeswitching strategies can support learning in shared book reading:

a study by Melanie Brouillard et al (2022) showed that children learned new words from monolingual or bilingual books, so book type didn’t affect vocabulary learning.

a study by Kirsten Read et al. (2020) showed that books that included some code-switching supported word learning in 5-year-olds.

For me Audio Books are someone reading a written book, word for word. Hörspiele are audio stories, not connected to a written book, almost like a podcast or audio story in you can find in meditation apps. They have been around in Germany for years - my husband and I listened to them on cassette tapes when we were little. It is often a series with the same characters - sometimes with the same person doing the different voices, other times with a cast of actors/actresses/sound bites so it sounds like a TV show. Benjamin Blümchen, Drei Fragezeichen, Kokonuss are all examples of Horspiele and I find them a super useful tool for exposing our kids to more German. They listen to them when playing Legos, in the car, before going to bed. Not sure if something like this exists in other languages!

Ici on aimerait bien enseigner le français à mon bébé qui est allemand, depuis que j’habite en Allemagne je ne parle plus très bien français, je n’ai personne avec qui échanger en français.